More recently non-representational approaches have emphasized the processual nature of utopias, yet studies have overlooked the experimental nature of these alternative spaces. Scholarship concerning intentional communities draws on utopian studies that consider them as utopian laboratories. In so doing, it grounds the analysis on the intentional community of Damanhur (Italy), as an example of experimental spaces. This paper analyses the experimental nature of alternative spaces and the affective, emotional and embodied experience their enactment generates.

Informed by writings by Ruth Levitas and Lucy Sargisson, it will then introduce the concept of 'utopia', to clarify this widely contested, variously applied and yet effectively used term (Levitas, 2003). First, it is going to describe the concept of ecovillages and provide an outline of the historical background of the movement. This paper will explore and analyse the ecovillage movement and the " Global Ecovillage Network " (GEN) in regards to their utopian characteristics. Supporters of the movement have called it " the most significant event of the 20th century " (Trainer in Jackson, R. They strive for sustainability, reject an over consumptive way of living and acknowledge the interdependence of people and nature. Communities living in " ecovillages " have taken this seriously for over thirty years. Collective action is required and for this, utopian thinking and the formation of groups can be helpful and motivating for individuals who are aiming towards the revision of values and behaviours concerning the environment. However, it is still not acted upon sufficiently and the lack of systematic policy-making prevents concrete action and intervention on a global scale (Giddens, 2009). In a 2011 article, Ramsden writes that Calhoun’s studies were brandished by others to justify population control efforts largely targeted at poor and marginalized communities.Climate change has been an issue for over a quarter of a century, but it has only been in the past years that global warming has been taken more seriously (Giddens, 2009).

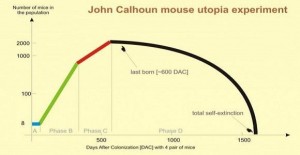

Population growth in the 1970s was swelling, and films such as Soylent Green tapped into growing fears of overpopulation and urban violence. “There’s no recovery, and that’s what was so shocking to ,” says Ramsden.Ĭalhoun wasn’t shy about anthropomorphizing his findings, binning rodents into categories such as “juvenile delinquents” and “social dropouts,” and others seized on these human parallels. Effectively, says Ramsden, they became “trapped in an infantile state of early development,” even when removed from Universe 25 and introduced to “normal” mice. Instead of interacting with their peers, males compulsively groomed themselves females stopped getting pregnant. Mice born into the chaos couldn’t form normal social bonds or engage in complex social behaviors such as courtship, mating, and pup-rearing. This iteration, dubbed Universe 25, was the first crowding experiment he ran to completion.Įventually Universe 25 took another disturbing turn. The only scarce resource in this microcosm was physical space, and Calhoun suspected that it was only a matter of time before this caused trouble in paradise.Ĭalhoun had been running similar experiments with rodents for decades but had always had to end them prematurely, ironically because of laboratory space constraints, says Edmund Ramsden, a science historian at Queen Mary University of London. In 1968, Calhoun had started the experiment by introducing four mouse couples into a specially designed pen-a veritable rodent Garden of Eden-with numerous “apartments,” abundant nesting supplies, and unlimited food and water. The results, laid bare at his feet, had taken years to play out.

Calhoun wasn’t the survivor of a natural disaster or nuclear meltdown rather, he was a researcher at the National Institute of Mental Health conducting an experiment into the effects of overcrowding on mouse behavior.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)